Free Bw Classic Turkish Cut Out Door Design Clip Art

A film editor at work in 1946

Film editing is both a creative and a technical office of the post-production process of filmmaking. The term is derived from the traditional process of working with pic which increasingly involves the utilise of digital applied science.

The film editor works with the raw footage, selecting shots and combining them into sequences which create a finished movement picture. Picture show editing is described every bit an art or skill, the only art that is unique to picture palace, separating filmmaking from other fine art forms that preceded it, although there are close parallels to the editing process in other art forms such as poetry and novel writing. Film editing is often referred to as the "invisible art"[1] considering when it is well-good, the viewer can become so engaged that they are not aware of the editor'south work.

On its about central level, film editing is the art, technique and practice of assembling shots into a coherent sequence. The job of an editor is non just to mechanically put pieces of a film together, cut off film slates or edit dialogue scenes. A moving picture editor must creatively work with the layers of images, story, dialogue, music, pacing, as well as the actors' performances to effectively "re-imagine" and even rewrite the film to craft a cohesive whole. Editors usually play a dynamic role in the making of a film. Sometimes, auteurist flick directors edit their own films, for example, Akira Kurosawa, Bahram Beyzai, Steven Soderbergh, and the Coen brothers.

With the advent of digital editing in non-linear editing systems, picture show editors and their assistants have become responsible for many areas of filmmaking that used to be the responsibility of others. For example, in past years, film editors dealt only with just that—picture show. Sound, music, and (more recently) visual effects editors dealt with the practicalities of other aspects of the editing process, normally under the direction of the movie editor and director. However, digital systems accept increasingly put these responsibilities on the film editor. It is common, peculiarly on lower budget films, for the editor to sometimes cutting in temporary music, mock upwardly visual effects and add temporary sound furnishings or other sound replacements. These temporary elements are ordinarily replaced with more refined terminal elements produced by the sound, music and visual effects teams hired to complete the film.

History [edit]

Early films were short films that were one long, static, and locked-downward shot. Motion in the shot was all that was necessary to amuse an audience, and then the showtime films simply showed activity such as traffic moving along a city street. There was no story and no editing. Each film ran as long as there was moving-picture show in the camera.

The use of film editing to found continuity, involving activeness moving from one sequence into another, is attributed to British motion picture pioneer Robert W. Paul's Come Forth, Exercise!, made in 1898 and one of the first films to characteristic more than than i shot.[two] In the first shot, an elderly couple is outside an fine art exhibition having lunch and and so follow other people within through the door. The 2d shot shows what they do inside. Paul's 'Cinematograph Camera No. one' of 1896 was the first camera to characteristic reverse-cranking, which allowed the aforementioned film footage to be exposed several times and thereby to create super-positions and multiple exposures. One of the first films to utilize this technique, Georges Méliès'due south The Four Troublesome Heads from 1898, was produced with Paul's photographic camera.

The further development of action continuity in multi-shot films continued in 1899-1900 at the Brighton Schoolhouse in England, where information technology was definitively established by George Albert Smith and James Williamson. In that yr, Smith made As Seen Through a Telescope, in which the main shot shows street scene with a fellow tying the shoelace and and so caressing the foot of his girlfriend, while an old man observes this through a telescope. There is then a cut to shut shot of the hands on the girl's foot shown inside a blackness circular mask, and and then a cut back to the continuation of the original scene.

Fifty-fifty more remarkable was James Williamson'due south Assail on a China Mission Station, fabricated effectually the same time in 1900. The first shot shows the gate to the mission station from the exterior beingness attacked and broken open by Chinese Boxer rebels, then there is a cut to the garden of the mission station where a pitched battle ensues. An armed party of British sailors arrived to defeat the Boxers and rescue the missionary's family. The moving-picture show used the first "reverse angle" cut in film history.

James Williamson concentrated on making films taking action from one place shown in one shot to the next shown in some other shot in films like Stop Thief! and Fire!, made in 1901, and many others. He likewise experimented with the shut-up, and made perhaps the most farthermost one of all in The Big Swallow, when his character approaches the camera and appears to eat information technology. These two filmmakers of the Brighton School also pioneered the editing of the picture; they tinted their work with color and used flim-flam photography to raise the narrative. By 1900, their films were extended scenes of up to 5 minutes long.[3]

Other filmmakers so took up all these ideas including the American Edwin South. Porter, who started making films for the Edison Company in 1901. Porter worked on a number of minor films before making Life of an American Fireman in 1903. The film was the showtime American picture show with a plot, featuring activity, and even a closeup of a hand pulling a fire alarm. The pic comprised a continuous narrative over seven scenes, rendered in a total of nine shots.[4] He put a dissolve between every shot, merely as Georges Méliès was already doing, and he ofttimes had the same action repeated across the dissolves. His motion picture, The Great Railroad train Robbery (1903), had a running time of twelve minutes, with 20 split up shots and ten dissimilar indoor and outdoor locations. He used cross-cutting editing method to show simultaneous activeness in unlike places.

These early film directors discovered important aspects of film language: that the screen epitome does non need to show a complete person from head to toe and that splicing together two shots creates in the viewer's mind a contextual relationship. These were the key discoveries that made all non-alive or non alive-on-videotape narrative motion pictures and television possible—that shots (in this case, whole scenes since each shot is a consummate scene) can exist photographed at widely different locations over a flow of time (hours, days or even months) and combined into a narrative whole.[5] That is, The Not bad Train Robbery contains scenes shot on sets of a telegraph station, a railroad automobile interior, and a dance hall, with outdoor scenes at a railroad water belfry, on the train itself, at a point along the rails, and in the woods. Just when the robbers get out the telegraph station interior (gear up) and emerge at the water belfry, the audience believes they went immediately from one to the other. Or that when they climb on the railroad train in i shot and enter the baggage car (a ready) in the adjacent, the audience believes they are on the same train.

Sometime around 1918, Russian director Lev Kuleshov did an experiment that proves this point. (See Kuleshov Experiment) He took an old film clip of a headshot of a noted Russian thespian and intercut the shot with a shot of a bowl of soup, then with a child playing with a teddy acquit, then with a shot an elderly adult female in a catafalque. When he showed the film to people they praised the actor'southward interim—the hunger in his confront when he saw the soup, the delight in the kid, and the grief when looking at the dead woman.[half dozen] Of grade, the shot of the actor was years before the other shots and he never "saw" any of the items. The simple act of juxtaposing the shots in a sequence made the human relationship.

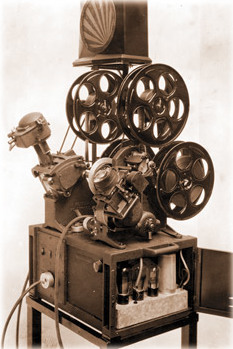

The original editing machine: an upright Moviola.

Film editing applied science [edit]

Before the widespread use of digital non-linear editing systems, the initial editing of all films was done with a positive copy of the picture show negative called a film workprint (cutting copy in UK) by physically cutting and splicing together pieces of film.[seven] Strips of footage would be paw cutting and attached together with record and and so afterwards in fourth dimension, glue. Editors were very precise; if they made a wrong cut or needed a fresh positive impress, it toll the production money and fourth dimension for the lab to reprint the footage. Additionally, each reprint put the negative at risk of damage. With the invention of a splicer and threading the machine with a viewer such as a Moviola, or "flatbed" motorcar such as a K.-East.-M. or Steenbeck, the editing procedure sped upwards a little bit and cuts came out cleaner and more precise. The Moviola editing practice is not-linear, allowing the editor to brand choices faster, a swell advantage to editing episodic films for television which have very brusk timelines to consummate the work. All film studios and production companies who produced films for television provided this tool for their editors. Flatbed editing machines were used for playback and refinement of cuts, particularly in feature films and films made for tv set because they were less noisy and cleaner to piece of work with. They were used extensively for documentary and drama product within the BBC's Flick Department. Operated past a team of two, an editor and assistant editor, this tactile process required meaning skill but allowed for editors to work extremely efficiently.[eight]

Acmade Picsynch for audio and picture coordination

Today, most films are edited digitally (on systems such as Media Composer, Last Cut Pro X or Premiere Pro) and bypass the flick positive workprint birthday. In the past, the use of a film positive (not the original negative) allowed the editor to do equally much experimenting every bit he or she wished, without the risk of damaging the original. With digital editing, editors can experiment only every bit much as before except with the footage completely transferred to a figurer hard bulldoze.

When the film workprint had been cut to a satisfactory state, it was and then used to make an edit determination list (EDL). The negative cutter referred to this list while processing the negative, splitting the shots into rolls, which were and then contact printed to produce the terminal moving picture print or reply print. Today, production companies have the option of bypassing negative cutting altogether. With the advent of digital intermediate ("DI"), the physical negative does non necessarily demand to exist physically cutting and hot spliced together; rather the negative is optically scanned into the reckoner(s) and a cut list is confirmed past a DI editor.

Women in flick editing [edit]

In the early years of film, editing was considered a technical chore; editors were expected to "cut out the bad $.25" and cord the picture show together. Indeed, when the Motion Picture Editors Guild was formed, they chose to exist "below the line", that is, not a creative guild, but a technical i. Women were not usually able to pause into the "creative" positions; directors, cinematographers, producers, and executives were almost always men. Editing afforded creative women a identify to assert their mark on the filmmaking procedure. The history of film has included many women editors such as Dede Allen, Anne Bauchens, Margaret Booth, Barbara McLean, Anne V. Coates, Adrienne Fazan, Verna Fields, Blanche Sewell and Eda Warren.[nine]

Mail service-production [edit]

Post-product editing may be summarized past iii distinct phases normally referred to equally the editor's cut, the managing director's cut, and the final cut.

There are several editing stages and the editor's cut is the outset. An editor's cutting (sometimes referred to as the "Associates edit" or "Crude cutting") is normally the first pass of what the terminal pic will be when it reaches picture lock. The pic editor unremarkably starts working while principal photography starts. Sometimes, prior to cut, the editor and director will have seen and discussed "dailies" (raw footage shot each twenty-four hours) as shooting progresses. As product schedules have shortened over the years, this co-viewing happens less often. Screening dailies requite the editor a general idea of the director's intentions. Considering it is the first pass, the editor's cutting might be longer than the final film. The editor continues to refine the cut while shooting continues, and frequently the entire editing process goes on for many months and sometimes more than a twelvemonth, depending on the film.

When shooting is finished, the managing director can then turn his or her total attention to collaborating with the editor and further refining the cut of the pic. This is the time that is set aside where the film editor'south first cut is molded to fit the director's vision. In the United States, nether the rules of the Directors Guild of America, directors receive a minimum of ten weeks after completion of principal photography to prepare their first cut. While collaborating on what is referred to every bit the "director's cut", the director and the editor go over the entire movie in great item; scenes and shots are re-ordered, removed, shortened and otherwise tweaked. Often it is discovered that at that place are plot holes, missing shots or even missing segments which might require that new scenes exist filmed. Because of this time working closely and collaborating – a period that is normally far longer and more intricately detailed than the unabridged preceding film production – many directors and editors grade a unique artistic bond.

Often afterwards the director has had their adventure to oversee a cutting, the subsequent cuts are supervised by one or more producers, who represent the production visitor or moving picture studio. There take been several conflicts in the by between the director and the studio, sometimes leading to the use of the "Alan Smithee" credit signifying when a director no longer wants to be associated with the final release.

Methods of montage [edit]

In move pic terminology, a montage (from the French for "putting together" or "assembly") is a film editing technique.

There are at least iii senses of the term:

- In French film practice, "montage" has its literal French meaning (assembly, installation) and just identifies editing.

- In Soviet filmmaking of the 1920s, "montage" was a method of juxtaposing shots to derive new meaning that did not be in either shot alone.

- In classical Hollywood cinema, a "montage sequence" is a short segment in a flick in which narrative data is presented in a condensed fashion.

Although flick director D.Westward. Griffith was not function of the montage school, he was one of the early proponents of the power of editing — mastering cantankerous-cutting to show parallel action in different locations, and codifying motion-picture show grammar in other means every bit well. Griffith'due south work in the teens was highly regarded by Lev Kuleshov and other Soviet filmmakers and greatly influenced their understanding of editing.

Kuleshov was among the get-go to theorize about the relatively immature medium of the picture palace in the 1920s. For him, the unique essence of the picture palace — that which could be duplicated in no other medium — is editing. He argues that editing a film is similar constructing a edifice. Brick-past-brick (shot-by-shot) the building (motion picture) is erected. His frequently-cited Kuleshov Experiment established that montage tin can lead the viewer to reach certain conclusions about the action in a moving-picture show. Montage works because viewers infer significant based on context. Sergei Eisenstein was briefly a student of Kuleshov'due south, but the two parted ways because they had different ideas of montage. Eisenstein regarded montage equally a dialectical means of creating pregnant. By contrasting unrelated shots he tried to provoke associations in the viewer, which were induced by shocks. Merely Eisenstein did not always practice his own editing, and some of his most important films were edited past Esfir Tobak.[10]

A montage sequence consists of a series of short shots that are edited into a sequence to condense narrative. Information technology is usually used to advance the story equally a whole (oft to suggest the passage of time), rather than to create symbolic meaning. In many cases, a vocal plays in the background to enhance the mood or reinforce the bulletin beingness conveyed. Ane famous case of montage was seen in the 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey, depicting the start of man'southward first development from apes to humans. Some other example that is employed in many films is the sports montage. The sports montage shows the star athlete grooming over a period of time, each shot having more improvement than the last. Classic examples include Rocky and the Karate Kid.

The word'due south association with Sergei Eisenstein is oftentimes condensed—likewise merely—into the idea of "juxtaposition" or into two words: "collision montage," whereby ii side by side shots that oppose each other on formal parameters or on the content of their images are cut against each other to create a new meaning not contained in the respective shots: Shot a + Shot b = New Significant c.

The association of standoff montage with Eisenstein is non surprising. He consistently maintained that the mind functions dialectically, in the Hegelian sense, that the contradiction betwixt opposing ideas (thesis versus antithesis) is resolved past a higher truth, synthesis. He argued that disharmonize was the basis of all fine art, and never failed to see montage in other cultures. For instance, he saw montage as a guiding principle in the structure of "Japanese hieroglyphics in which 2 independent ideographic characters ('shots') are juxtaposed and explode into a concept. Thus:

Center + Water = Crying

Door + Ear = Eavesdropping

Child + Rima oris = Screaming

Mouth + Dog = Barking.

Mouth + Bird = Singing."[11]

He also constitute montage in Japanese haiku, where short sense perceptions are juxtaposed, and synthesized into a new significant, every bit in this example:

- A lonely crow

- On a leafless bender

- One autumn eve.

- On a leafless bender

(枯朶に烏のとまりけり秋の暮)

-- Matsuo Basho

As Dudley Andrew notes, "The standoff of attractions from line to line produces the unified psychological effect which is the authentication of haiku and montage."[12]

Continuity editing and alternatives [edit]

Continuity is a term for the consistency of on-screen elements over the grade of a scene or motion-picture show, such equally whether an actor's costume remains the same from one scene to the next, or whether a glass of milk held by a graphic symbol is total or empty throughout the scene. Because films are typically shot out of sequence, the script supervisor will keep a record of continuity and provide that to the film editor for reference. The editor may try to maintain continuity of elements, or may intentionally create a discontinuous sequence for stylistic or narrative effect.

The technique of continuity editing, role of the classical Hollywood way, was developed past early European and American directors, in particular, D.W. Griffith in his films such as The Nascence of a Nation and Intolerance. The classical style embraces temporal and spatial continuity as a way of advancing the narrative, using such techniques as the 180 caste dominion, Establishing shot, and Shot reverse shot. Ofttimes, continuity editing means finding a balance betwixt literal continuity and perceived continuity. For instance, editors may condense activity across cuts in a non-distracting manner. A character walking from one identify to another may "skip" a section of floor from ane side of a cut to the other, but the cut is synthetic to announced continuous so as not to distract the viewer.

Early on Russian filmmakers such as Lev Kuleshov (already mentioned) further explored and theorized about editing and its ideological nature. Sergei Eisenstein developed a system of editing that was unconcerned with the rules of the continuity system of classical Hollywood that he called Intellectual montage.

Alternatives to traditional editing were likewise explored by early surrealist and Dada filmmakers such equally Luis Buñuel (managing director of the 1929 Un Chien Andalou) and René Clair (manager of 1924'southward Entr'acte which starred famous Dada artists Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray).

The French New Wave filmmakers such as Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut and their American counterparts such as Andy Warhol and John Cassavetes also pushed the limits of editing technique during the late 1950s and throughout the 1960s. French New Wave films and the non-narrative films of the 1960s used a carefree editing mode and did not adjust to the traditional editing etiquette of Hollywood films. Similar its Dada and surrealist predecessors, French New Wave editing often drew attention to itself by its lack of continuity, its demystifying self-reflexive nature (reminding the audition that they were watching a film), and by the overt utilize of jump cuts or the insertion of textile not often related to whatever narrative. Three of the virtually influential editors of French New Wave films were the women who (in combination) edited 15 of Godard's films: Francoise Collin, Agnes Guillemot, and Cecile Decugis, and some other notable editor is Marie-Josèphe Yoyotte, the beginning black woman editor in French cinema and editor of The 400 Blows.[10]

Since the late 20th century Post-classical editing has seen faster editing styles with nonlinear, discontinuous activeness.

Significance [edit]

Vsevolod Pudovkin noted that the editing procedure is the 1 phase of production that is truly unique to motion pictures. Every other attribute of filmmaking originated in a different medium than film (photography, fine art direction, writing, sound recording), merely editing is the one procedure that is unique to film.[thirteen] Filmmaker Stanley Kubrick was quoted as maxim: "I love editing. I think I like it more any other phase of filmmaking. If I wanted to be frivolous, I might say that everything that precedes editing is merely a fashion of producing a film to edit."[14]

According to writer-director Preston Sturges:

[T]here is a constabulary of natural cutting and that this replicates what an audience in a legitimate theater does for itself. The more nearly the film cutter approaches this law of natural interest, the more than invisible will be his cutting. If the camera moves from one person to another at the exact moment that one in the legitimate theatre would accept turned his head, i volition non exist conscious of a cut. If the camera misses by a quarter of a 2nd, one will get a jolt. There is i other requirement: the 2 shots must be approximate of the same tone value. If 1 cuts from blackness to white, it is jarring. At any given moment, the camera must point at the exact spot the audience wishes to look at. To find that spot is absurdly easy: i has only to remember where i was looking at the fourth dimension the scene was fabricated.[15]

Assistant editors [edit]

Banana editors aid the editor and director in collecting and organizing all the elements needed to edit the moving picture. The Move Picture Editors Guild defines an assistant editor every bit "a person who is assigned to assist an Editor. His or her duties shall be such as are assigned and performed under the immediate direction, supervision, and responsibleness of the editor."[16] When editing is finished, they oversee the various lists and instructions necessary to put the flick into its final class. Editors of large budget features will commonly take a squad of assistants working for them. The first banana editor is in charge of this team and may do a pocket-size bit of picture editing also, if necessary. Oft assistant editors will perform temporary audio, music, and visual effects work. The other administration will have set tasks, ordinarily helping each other when necessary to consummate the many time-sensitive tasks at mitt. In addition, an amateur editor may exist on paw to aid the administration. An apprentice is usually someone who is learning the ropes of profitable.[17]

Television shows typically have one banana per editor. This banana is responsible for every chore required to bring the show to the last grade. Lower upkeep features and documentaries volition as well commonly accept only one assistant.

The organizational aspects job could best be compared to database management. When a movie is shot, every piece of flick or audio is coded with numbers and timecode. Information technology is the assistant's job to keep rails of these numbers in a database, which, in non-linear editing, is linked to the computer program.[ citation needed ] The editor and director cut the film using digital copies of the original motion-picture show and sound, ordinarily referred to as an "offline" edit. When the cut is finished, it is the assistant's chore to bring the picture show or television show "online". They create lists and instructions that tell the picture and sound finishers how to put the edit back together with the loftier-quality original elements. Assistant editing can be seen as a career path to eventually becoming an editor. Many assistants, all the same, exercise not choose to pursue advocacy to the editor, and are very happy at the assistant level, working long and rewarding careers on many films and telly shows.[18]

Come across also [edit]

- 180-degree rule

- 30-degree rule

- Footage (A Roll)

- B-scroll

- Cinematic techniques

- Clapperboard

- Compositing (keying)

- Cut (transition), for the managing director'south call Cutting! or stop

- Axial cut

- Cantankerous-cut

- Fast cutting

- Jump cut

- Long take

- Match cut

- Tedious cutting

- Cutaway

- The Cutting Edge: The Magic of Movie Editing

- Edit decision listing (EDL)

- Film transition

- Deliquesce

- L cut (split edit)

- Wipe

- Filmmaking

- Alphabetize of articles related to motion pictures

- Kuleshov effect

- Picture Editors Guild (MPEG)

- Moviola

- Negative cutting

- Outline of film

- Re-edited movie

- Scene

- Sequence

- Shot

- Crane shot

- Establishing shot

- Insert

- Master shot

- Point-of-view shot

- Shot reverse shot

- Video editing

References [edit]

Notes

- ^ Harris, Mark. "Which Editing is a Cut To a higher place?" The New York Times (Jan 6, 2008)

- ^ Brooke, Michael. "Come Along, Do!". BFI Screenonline Database . Retrieved 2011-04-24 .

- ^ "The Brighton Schoolhouse". Archived from the original on 2013-12-24. Retrieved 2012-12-17 .

- ^ Originally in Edison Films catalog, Feb 1903, two–3; reproduced in Charles Musser, Before the Nickelodeon: Edwin S. Porter and the Edison Manufacturing Visitor (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991), 216–18.

- ^ Arthur Knight (1957). p. 25.

- ^ Arthur Knight (1957). pp. 72–73.

- ^ "Cut Room Practice and Procedure (BBC Film Training Text no. 58) – How television receiver used to be made". Retrieved 2019-02-08 .

- ^ Ellis, John; Hall, Nick (2017): Suit. figshare. Collection.https://doi.org/10.17637/rh.c.3925603.v1

- ^ Galvão, Sara (March 15, 2015). ""A Tedious Job" – Women and Flick Editing". Critics Associated via.hypothes.is . Retrieved 2018-01-15 .

- ^ a b "Esfir Tobak". Edited by.

- ^ S. M. Eisenstein and Richard Taylor, Selected works Volume one, (Bloomington: BFI/Indiana University Press, 1988), 164.

- ^ Dudley Andrew, The major film theories: an introduction (London: Oxford University Press, 1976), 52.

- ^ Jacobs, Lewis (1954). Introduction. Picture technique ; and Film acting : the cinema writings of V.I. Pudovkin. By Pudovkin, Vsevolod Illarionovich. Vision. p. ix. OCLC 982196683. Retrieved March xxx, 2019 – via Internet Annal.

- ^ Walker, Alexander (1972). Stanley Kubrick Directs. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. p. 46. ISBN0156848929 . Retrieved March 30, 2019 – via GoogleBooks.

- ^ Sturges, Preston; Sturges, Sandy (adapt. & ed.) (1991), Preston Sturges on Preston Sturges, Boston: Faber & Faber, ISBN0-571-16425-0 , p. 275

- ^ Hollyn, Norman (2009). The Film Editing Room Handbook: How to Tame the Chaos of the Editing Room. Peachpit Press. p. xv. ISBN978-0321702937 . Retrieved March 29, 2019 – via GoogleBooks.

- ^ Wales, Lorene (2015). Complete Guide to Picture show and Digital Production: The People and The Process. CRC Printing. p. 209. ISBN978-1317349310 . Retrieved March 29, 2019 – via GoogleBooks.

- ^ Jones, Chris; Jolliffe, Genevieve (2006). The Guerilla Film Makers Handbook. A&C Black. p. 363. ISBN082647988X . Retrieved March 29, 2019 – via GoogleBooks.

Bibliography

- Dmytryk, Edward (1984). On Film Editing: An Introduction to the Fine art of Film Construction. Focal Press, Boston. ISBN 0-240-51738-v

- Eisenstein, Sergei (2010). Glenny, Michael; Taylor, Richard (eds.). Towards a Theory of Montage. Michael Glenny (translation). London: Tauris. ISBN978-i-84885-356-0. Translation of Russian linguistic communication works past Eisenstein, who died in 1948.

- Knight, Arthur (1957). The Liveliest Art. Mentor Books. New American Library. ISBN 0-02-564210-3

Further reading

- Morales, Morante, Luis Fernando (2017). 'Editing and Montage in International Film and Video: Theory and Technique, Focal Press, Taylor & Francis ISBN 1-138-24408-2

- Murch, Walter (2001). In the Blink of an Centre: a Perspective on Film Editing. Silman-James Press. 2d rev. ed.. ISBN 1-879505-62-ii

External links [edit]

- Sit-in of Picsync machine past former BBC film editors

- Sit-in of editing 16mm pic using a Steenbeck editing tabular array

- Discussion and demonstration of a 16mm edit suite and the working environment within it

Wikibooks

- Mewa Flick User'southward Guide

- Movie Making Manual

Wikiversity

- Portal:Filmmaking

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Film_editing

Post a Comment for "Free Bw Classic Turkish Cut Out Door Design Clip Art"